Archives Hub feature for January 2020

On the evening of 12 January 1820, a group of men dined together at the Freemason’s Tavern in London, and resolved to establish the Astronomical Society of London, now known as the Royal Astronomical Society. One of its founding members was John F. W. Herschel (1792-1871). His father, William Herschel (1738-1822), was the Society’s first president, and his aunt, Caroline Herschel, (1750-1848) was one of the first women whose scientific achievements were recognised by the Society. Thanks to the generous donations of the Herschel family in the 20th century, the Royal Astronomical Society is the custodian of a significant collection of the astronomy-related papers of William, Caroline and John Herschel. At the beginning of the bicentenary year, we reflect on the Herschels’ relationship with the Royal Astronomical Society and the family’s contributions to astronomy.

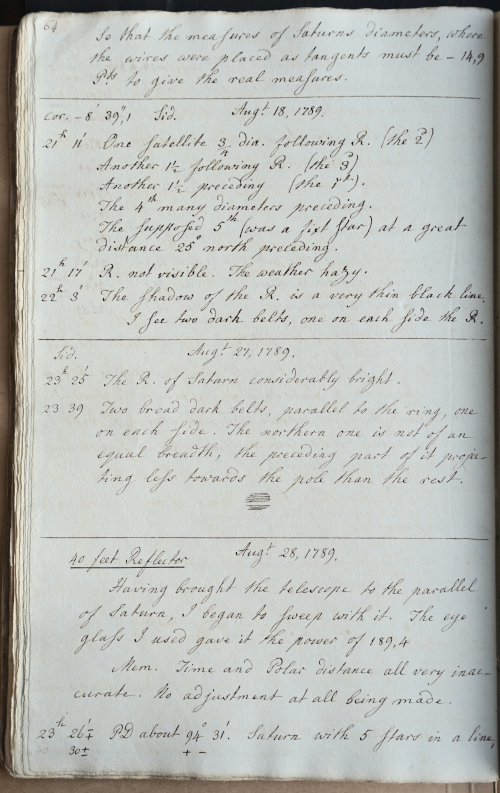

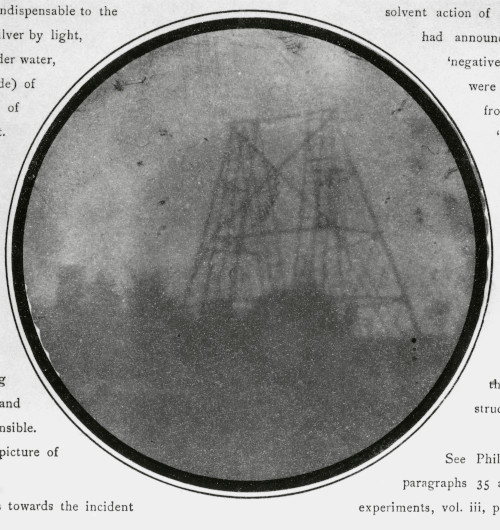

William grew up in Hanover in Germany and followed his father and older brother Jacob by joining the band of the Hanoverian Guards. When Hanover was occupied by French soldiers in 1757, William and Jacob were sent by their father to England as refugees from war. William settled in England and made a living as an itinerant musician in the North of England, before taking a post of organist in Bath in 1766. From the late 1760s he developed a serious interest in astronomy, eventually constructing his own telescopes in order to achieve the precision he desired for his observations. The largest of his telescopes was 40 feet in length, supported by a large wooden apparatus. A self-taught astronomer, he did not regard the stars as a mere fixed backdrop to the orbits of the planets like most of his peers. He was fascinated by the stellar universe and devised a systematic observation programme. Because he methodically observed every star of a certain magnitude, on 13 March 1781 he noticed a bluish disc-like object which did not look like an ordinary star. At first he identified this new object as a comet, but once enough data was available to calculate its orbit, it became clear that William Herschel had discovered a new planet. Originally named Georgium Sidus after George III, the planet is now known as Uranus. William was appointed astronomer to the King and continued his astronomical work, not only making new discoveries such as the moons of Saturn now known as Enceladus and Mimas, but also contributing to understanding of the structure of the heavens. His expertise spanned observation, instrument making, and theoretical astronomy.

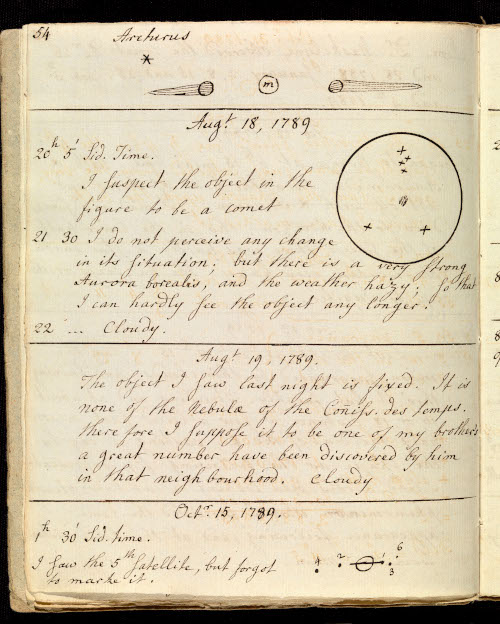

William Herschel’s achievements depended in large part on the assistance of his sister Caroline. The youngest of the ten Herschel siblings, she appeared destined to providing domestic assistance to her mother in Hanover, until William offered her the choice of moving to Bath in 1772 to train as a singer and manage his household. Caroline Herschel’s musical career as a soloist showed early promise, but by this time William was becoming preoccupied with astronomical work and increasingly relied on his sister for assistance with his observations. However, Caroline Herschel developed as an astronomer in her own right, as well, making numerous discoveries of comets and nebulae. From 1787, she received an income from the King, making her one of the first women to be paid for scientific work. She was the first woman to receive the gold medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1828 in recognition of the enormous contribution she had made by completing a catalogue of 2,500 nebulae. She became one of the first female honorary members of the RAS, at the same time as Mary Somerville in 1835.

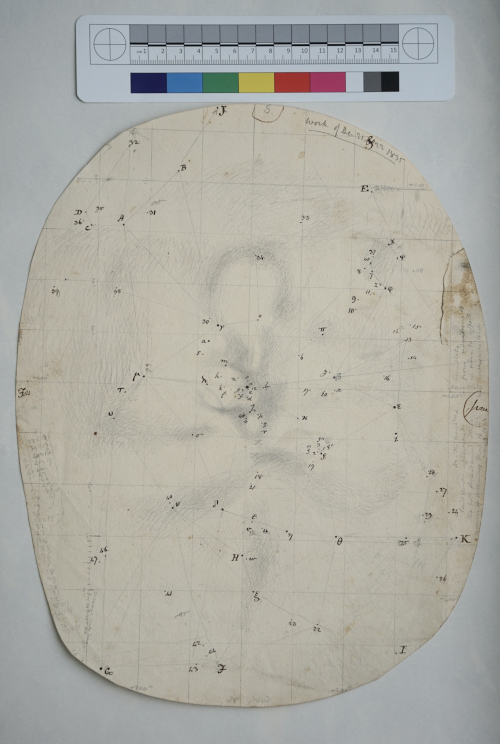

John F. W. Herschel initially pursued a career in law, but followed in the footsteps of his father, and was also strongly influenced by his aunt Caroline. He was a polymath who carried out significant work in other subjects such as mathematics and chemistry. As an undergraduate at the University of Cambridge he made friends with Charles Babbage, and both of them were among the founders of the Astronomical Society of London in 1820. One obstacle during the early days of the Society occurred when the Duke of Somerset was dissuaded by from taking on the Presidency of the Society by Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society. In the end, William Herschel agreed to be the first President, on the understanding that he should not be called upon for active service due to his advanced years. His son John Herschel would go on to serve as President of the Society three times. He dedicated himself to continuing and expanding upon his father’s programme of observations. From 1834 to 1838, he lived in South Africa with his family and catalogued the stars, nebulae and other celestial bodies of the southern skies, publishing his observations in Results of astronomical observations made during the years 1834, 5, 6, 7, 8, at the Cape of Good Hope […](1847).

On John Herschel’s return to England, he became involved in photography, not only coining the name of this new technology (as well as the terms ‘positive’ and ‘negative’), but by inventing processes such as the cyanotype process, and providing leadership and support to other practitioners in the field. The RAS archives holds a positive print of one of his experimental photographs of his father’s 40-foot telescope, taken shortly before it was decommissioned in 1839; the structure of this instrument lives on in the Royal Astronomical Society’s gold medal and seal.

The Royal Astronomical Society is not the only repository of Herschel family archives; other holding institutions are signposted by the William Herschel Society http://www.williamherschel.org.uk/herschel-resources/. As part of the celebrations of the Royal Astronomical Society bicentenary, from February to December 2020 an exhibition focused on John Herschel’s observations of nebulae will take place at the Herschel Museum in Bath, the former home of John Herschel’s father and aunt.

Dr Sian Prosser

Librarian and Archivist

Royal Astronomical Society

Related

Browse all Royal Astronomical Society Archives descriptions available to date on the Archives Hub.

All images copyright Royal Astronomical Society Archives. Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.